22 Sep Jacques Pépin: Chef, Author, Artist

Editor’s note: Jacques Pépin’s experience as a chef, author, and mentor spans almost eight decades and is still going strong. Learn more about and be inspired by Jacques Pépin in this feature article, how he’s inspired my life and our favorite recipes: More Pepin: Personal Story, Books, Recipes

Les Legumes. Painting by Jacques Pepin

“You can go into an art studio and mix yellow and red. Does that make you an artist? You are first a craftsman. With talent you become an artist,” said Jacques Pépin, one of the world’s greatest chefs, who should know. He honed his craft and developed his talent over 83 years as a chef, author, TV celebrity, culinary instructor, and even as a painter.

Jacques Pepin, teacher, with student at Boston University culinary arts program

Pépin is best known as the author of 29 cookbooks, including Jacques Pépin Complete Technique, the updated Jacques Pépin New Complete Technique, Essential Pépin: More Than 700 All-Time Favorites from My Life in Food, and, most recently, Menus: A Book for Your Meals and Memories.

Many people are not aware of his other skill as an artist.

The winner of 16 James Beard Awards, Pépin has starred in 13 PBS cooking shows out of his 26 shows over 35 years. In 2004, Pépin was awarded France’s highest distinction, the Legion of Honor. For over 30 years, he has taught at Boston University where he developed the culinary arts program, BU Food and Wine, along with Julia Child and the program’s founding director, Rebecca Alssid.

Pépin’s youthful demeanor, winning smile, and rugged good looks belie a man in his eighth decade.

Here is a man, who along the way, has survived a life-threatening car crash resulting in multiple fractures, a mild stroke, and hip replacement, but he keeps going and never gives up. Standing for two hours to teach cooking classes is still part of his routine. Pépin is certainly an inspirational “poster boy” for successful aging.

Being a Great Chef

Pépin’s views on what makes a great chef are similar to his views on being a talented artist. “I don’t believe a professional chef can be a professional chef without being a technician first. That said, I know a fair amount of chefs who are technical but do not have talent,” he said.

It is perhaps for this reason that Pépin has stressed the importance of learning techniques—the basics of cooking and art—throughout his teachings, cookbooks, and art.

Pépin’s rise from a blue-collar kitchen apprentice in France to a world-renowned chef and recognized artist is an amazing story.

To begin to know Pépin, a good place to start is to read his memoir, The Apprentice: My Life in the Kitchen.

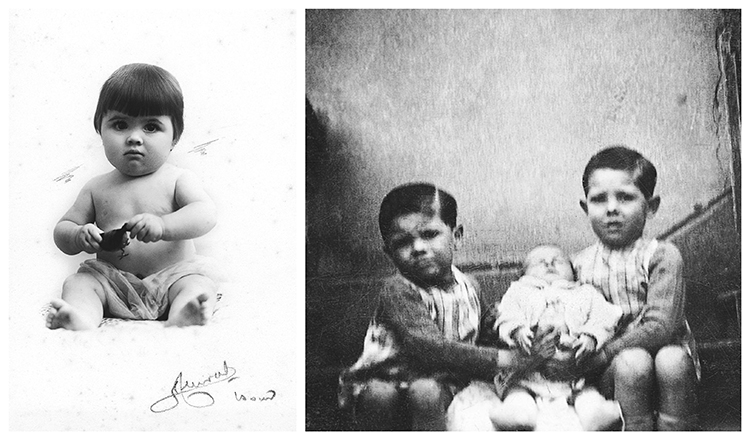

(Left) Jacques Pepin, at eight months, holding a toy chicken. (Right) Jacques and brother, Roland, holding brother Bichon.

Early Life

Pépin was born in 1935 in Bourg-en-Bresse, France, 43 miles northeast of Lyon and at the base of the Jura Mountains. Nicknamed “Tati” by one of his brothers, he was raised in a close-knit family. His father, Jean-Victor Pépin, was initially a cabinet maker, and his mother, Jeannette Pépin, would be labeled a skilled entrepreneur by today’s standards. He was the middle son of two brothers, Bichon Pépin and Roland Pépin.

“Mamam,” Pépin said, “was strikingly beautiful, with proud, erect posture, high cheekbones, large brown eyes and masses of black curls swept from her forehead. She was a tiny, wrenlike bundle of energy, always on the move.” Perhaps, Pépin became very much like his mother throughout his life.

Family at Chez Pepin

At age six, he was exposed to cooking while at his mother’s side. She opened a restaurant, Hotel L’Amour. This was her first entrepreneurial venture, and she only had the skill of a waitress combined with cooking for her family during wartime rationing and food scarcity.

Alongside his father, Pépin foraged for wild mushrooms and was exposed to wine-making. Summers were spent working on farms, receiving food and board in exchange for doing chores. It was there that he began to learn about local food sources. He attended boarding school but left school early to follow his passion by working in restaurants.

Life during the early war years was at the height of Italy’s war with France, headed up by Benito Mussolini, the fascist prime minister of Italy at the time. Pépin experienced the bombing of Bourg-en-Bresse when his apartment was decimated by the blasts, forcing his mother and brothers to flee. His home was bombed a second time by retreating Germans. He remembers vividly the liberation of Paris being celebrated in his town with an Allied tank coming through and American soldiers throwing chewing gum and candy. For Pépin, it was his first taste of milk chocolate.

At age 13 1/2, Pépin quit school to become an apprentice in a restaurant. As he said, “[I] was an ‘old’ thirteen. I was hardened by the war with its restrictions and bombings with stints away from home and the long absences of Papa,” At this young age, Pépin had already worked in four restaurants and knew that he wanted to be a chef. And so, he started his first apprenticeship in Bourg, France, at the Grand Hôtel de l’Europe.

Next stop was Paris to work at the famed Hôtel Plaza Athénée. It was there that he continued to fine-tune his understanding of the techniques of cooking rather than memorizing recipes. He rotated through the brigade de cuisine (kitchen stations), working with the poissonier (fish cook); the garde manger (keeper of the food) where he prepared food to be cooked, such as cleaning fish and trimming lamb; and the saucier (sauce chef) where he helped prepare sauces.

Military

Pépin was drafted into the military when France was at war with Algeria, which was seeking its independence. He was assigned to Paris to work at the officer’s mess at the Navy’s headquarters, fittingly called the Pépinière. He was brought on to the French office of the treasury first as an assistant chef and then as head chef to Félix Gaillard, the minister of finance. Four months later, the French government toppled, and Gaillard became France’s prime minister. After several more changes in France’s government, Pépin found himself as head chef to then-president of France Charles de Gaulle.

New York

Finishing his military service, Pépin decided to “visit” the United States. This visit has lasted 60 years.

In 1959, at age 23, he secured his first job with the renowned New York restaurant Le Pavillon under Pierre Franey, who would later become famous for his own cooking shows and his “60 Minute Gourmet” column in the New York Times.

While at Le Pavillon, Pépin came to a life-changing crossroads. He was offered the job of White House chef under then-U.S. President John F. Kennedy and simultaneously received a job offer from Howard Johnson, the founder of the famous Howard Johnson’s restaurant chain. Pépin decided to go with Johnson because he had already worked for heads of state with little national or international attention. This was a decision he said he never regretted.

Pépin joined Franey to help Johnson develop new products. He traded in making beef Burgundy for 12 for making clam chowder in 2,500-portion batches. Pépin leaped from dealing in cups, ounces, and teaspoons to gallons, tons, and bushels. For ten years, Pépin learned about food service American-style. He said he still makes New England clam chowder from his “Ho Jo” days … in smaller portions, of course.

Arriving in the U.S. without knowing how to speak English, Pépin enrolled in an English for foreign students course at Columbia University in New York. As a young man who had not completed high school, he decided to apply to Columbia’s School for General Studies for Adults. He was accepted to the program and later graduated. He must have been the perfect lab partner for biology, where rather than dissecting a rabbit, he boned it.

Following Howard Johnson’s, Pépin opened the first soup and salad restaurant in the U.S., La Potagerie on Fifth Avenue in New York in the spring of 1970.

Standing in a restaurant kitchen came to a sudden end for Pépin in 1974 when he was in a horrific car crash, hitting a deer and flipping the car, which exploded. He broke his back and was left with 14 fractures.

After a year of recovery and soul-searching, he decided to focus more on teaching and writing. In addition to the Boston University culinary program, Pépin co-founded the French Culinary Institute in 1984, which would later become the International Culinary Center in New York’s SoHo district. The school has been the launchpad for celebrity chefs such as Bobby Flay, Dan Barber, and Christina Tosi.

Wedding day with Gloria at Craig Claiborne’s house, 1966.

Family Life

During the 1960s and 1970s, many French chefs from the New York area gravitated upstate to Hunter Mountain. Pépin became a ski instructor and met his wife, Gloria, there, to whom he has been married for 53 years. They have one daughter, Claudine Pépin, who was his partner for two of his cookbooks (Jacques Pépin’s Kitchen: Cooking with Claudine and Jacques Pépin’s Kitchen: Encore with Claudine) and was his co-host for PBS cooking shows.

Claudine and her husband, Rolland “Rolley” Bailey Wesen, married in 2003 and have one daughter who has also been the inspiration for a cookbook, A Grandfather’s Lessons: In the Kitchen with Shorey.

Chef’s Ski Race for Jacques

What started as a fun race between small groups of New York chefs who also chose Hunter for their getaway destination became the US Chefs Ski Race.

In 1975, the year following Pépin’s accident, the Chefs Ski Race was started by famous ski school director Karl Plattner and organized by restaurateur Jacky Ruette. It attracted an all-star group of chefs and restaurateurs, including André Soltner of Lutèce, Seppi Renggli of the Four Seasons, Sirio Maccioni of Le Cirque, and the late Pierre Franey, a long-time friend of Pépin’s.

The race was inaugurated to honor Jacques Pépin. The event celebrated its 40th anniversary this past ski season.

Jacques Pepin’s painting, “Jean Michel’s Dining Room”

The Artist Within

During stays at Hunter Mountain, Pépin and Gloria would often restore old furniture. In 1962, he started dabbling in painting. He said, “I’ve been painting for 60 years.”

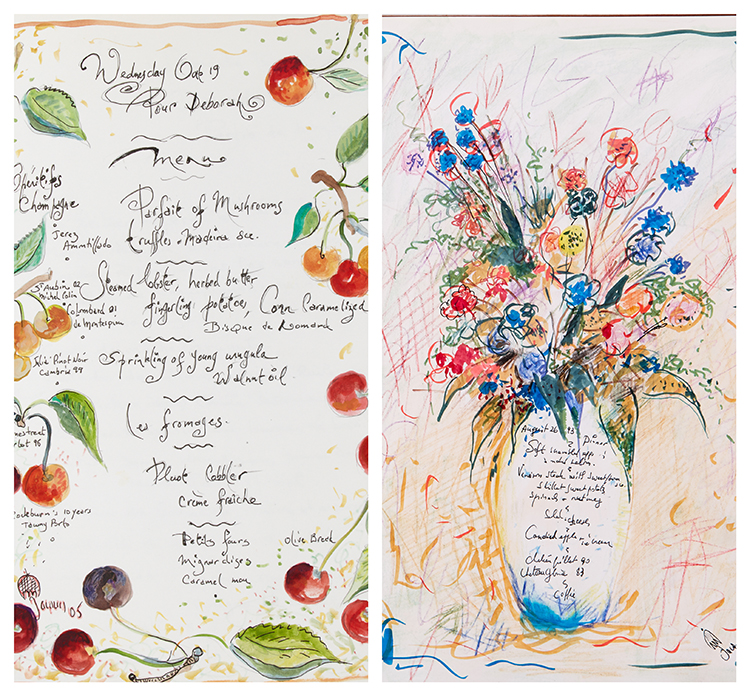

Pepin’s art started with menus.

It started with menus. Whether preparing a meal for his friends and family or a gala event for a celebrity host, the hand-written menu and colorful illustrated border became a signature of the meal as sentimental as the chef who created it. Over the years, the collection grew into 12 thick books of menus.

When he flips through the pages, he reminisces about the menu he drew for his daughter’s fourth birthday—with her handprint in the middle—made by dipping her hand in a plate of red wine. For other events, he also noted the wine itself, sometimes with the label. Guests would sign it, and, for special meals out, so would the chef who prepared it.

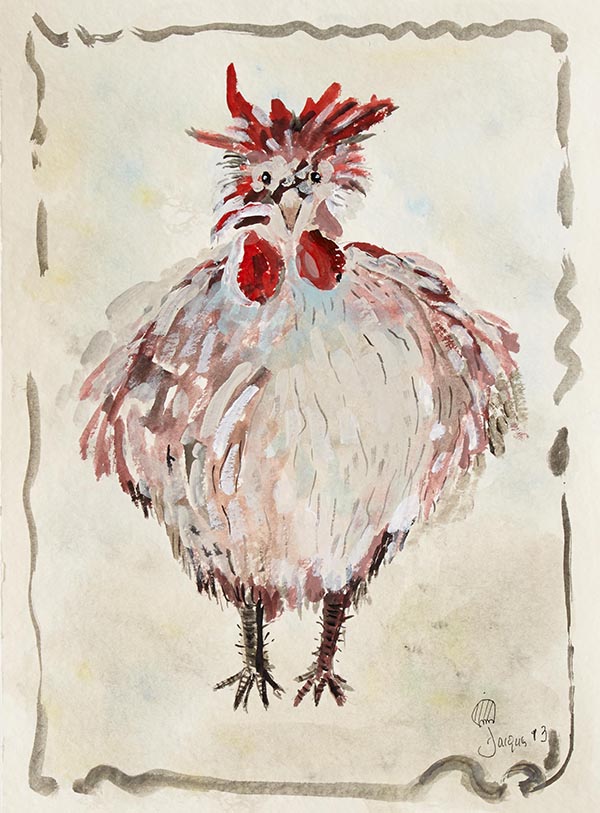

“The Cock” painting by Jacques Pepin

Some of Pépin’s menus have been turned into limited-edition prints using a giclée technique that requires specially formulated inks and specialty papers, resulting in the highest possible quality for each print. Just like any meal coming from Pépin’s kitchen, if his name is attached to it, quality is expected.

Many years ago, an art critic showed up at an informal showing of Pépin’s work and assumed that the pieces were created by five different painters. The styles were that different. When Jacques replied that everything, from realistic to impressionist and abstract, was all his, the critic was astonished.

Jean Pierre’s Kitchen Acrylic on canvas. Painting by Jacques Pepin

His method? “The process is intuitive,” Pépin said. Just like cooking. “It feels right, it belongs there, and it fits, just as a cook adds a dash of salt, pepper, or wine to a sauce to get the taste exactly right. You cannot suppress the subconscious, certainly in art, especially abstract or surrealistic, where the unconscious or subconscious is the source of inspiration.”

Although Pépin sees the similarity between cooking and painting because you use your hands for both, one obvious difference is that a meal is gone after you eat it. You can replicate it to a point, but the feeling and the mood and the subtle flavor differences of each fresh ingredient mean that each meal is savored and enjoyed, and then it’s gone, leaving a memory. A painting, on the other hand, stays with you and brings that feeling back every time you look at it.

Pigs. Painting by Jacques Pepin.

Whether a culinary-inspired seasonal menu, an interpretation of fresh flowers, a glimpse outside the window, or one of the many fun chickens and roosters from Pépin’s Chicken Coop Farm-to-Frame collection, the sentimental side of Jacques Pépin is visible through the artistry of Jacques Pépin.

“I don’t know whether my painting has helped my cuisine, or whether my cooking has helped my painting, and I don’t know if one borrows from the other,” said Pépin. “All I know is that, certainly for me, cooking and painting can live in harmony together. Both are different expressions of who I am and both enhance my life considerably.”

On his website, Jacques Pépin Art jacquespépinart.com, his artistry is offered in the forms of original art, limited-edition, signed fine-art prints, gallery-size prints, hand-drawn menu prints, and small gift sets.

Giving Back

Three years ago, in 2016, with Claudine and Rolley Wesen, the Jacques Pépin Foundation was created. This provided an opportunity for the Pépin family to give back to the community. The mission is to support community kitchens that offer free life skills and culinary training to adults who have difficulty finding employment. The programs offer help to those who were previously incarcerated, homeless, involved in substance abuse, who have low skill or education level, or a lack of work history.

To answer “what makes a great chef,” you need to understand the breadth of the chef’s career. It must be more than a technician or a talented creator. The answer resides in Pépin, who has done it all and has kept going.

The secret to his longevity can be summed up in his words,

“I like copious glasses of wine with my food and I do not like to eat alone.

I need family and friends to enjoy the dishes and the pleasure of dining.”

To learn more about Jacques Pepin’s art, click here.

To try some of Jacques Pepin’s recipes, see some recipes below.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.