By Dustin Grooms, Ph.D. and Jimmy Onate, Ph.D.

It may be the best known injury in sports—barely a week goes by without a leading athlete getting sidelined by a torn ACL. A key ligament deep within the knee, the anterior cruciate ligament is subjected to some of the most brutal forces in athletics.

For some time, we in sports medicine have noticed that for patients who tear an ACL, recovery can be slow and cautious. To find out why, we conducted a controlled study of athletes at The Ohio State University, and found that the injury does more than keep you off your feet—it can change the way your brain controls movement. Left unaddressed, the changes become a distraction, impairing performance and raising the likelihood of future injury.

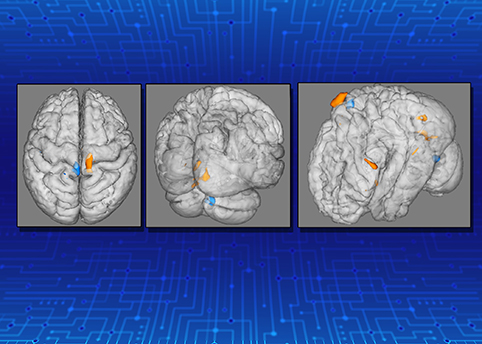

Scans taken in real time show how knee injuries change the brain, making patients rely more on visual cues for movement instead of natural instincts.

Watching the Brain in Action

One of the most powerful tools for studying the brain, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is revolutionizing health and science. When scanned in an fMRI machine, a patient is awake and alert as researchers watch blood flow shift around within the brain. With every movement or thought, the blood travels to the most active neurons, creating precise brain images for everything from thinking about a soccer ball to raising a leg.

For our study at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, we recruited a number of athletes willing to sit through an fMRI scan at the university’s Center for Cognitive Brain Behavior Imaging.

Half the volunteers had experienced ACL injuries at some point in their lives, and half had not— though all were in top physical shape and any physical ACL injuries had long ago healed.

Control was important, so we made sure that for every recovered ACL patient, there was an athlete of similar age, height, weight, and athletic experience.

During the experiment, each volunteer lay within the fMRI machine with his legs exposed and able to move freely. During analysis, each athlete moved his leg in a simple up and down motion, flexing at the knee.

As we watched brain activity, we could see which parts were activated when and immediately saw differences between patients who had once had ACL injuries and those who hadn’t. The result was obvious, even though the task was as basic as bending a knee. While some changes involved how the brain processes pain, the critical breakthrough was realizing that injured ACLs led to a shift in brain activity to regions that process visual information during movement that help keep you on track.

Knee injuries lead to changes in the brain, according to a new study from The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center.

Seeing Is Believing, but It Isn’t Efficient

From our findings, we realized that patients’ brains had compensated for ACL injuries by relying more on vision than proprioception. Patients no longer trusted their knees—the athletes tended to look at their legs and rely on cues from their surroundings instead of trusting the sensory feedback and instinctive movements they had been using since before learning to walk.

It’s as if these athletes were moving around in the dark, relying on visual cues instead of tactile feedback, lacking confidence and precision.

That adaptation makes sense. After an ACL injury, you still want to walk, you still want to play with your kids, you still want to participate in your sport or do anything else. Your brain is powerful, and it’s going to find a way to get those tasks done, even if the feedback it’s getting from your joints or from the injured area is disrupted.

Instead of movement as second nature—literally what allows us to walk and chew gum at the same time—patients who have had an ACL injury tend to overthink movement. It’s such a strong effect that we see it in rehabilitation all the time, and it’s enough of a distraction that it can set patients up for further injury.

Researchers observe brain scans in real time as a patient moves his knee during an MRI. A new study shows knee injuries cause changes in the brain and alter the way patients move after they heal.

Managing the Mind

Now that we’ve carefully identified the problem, the next phase of our work will be to try to reverse the changes.

One technology we’ve begun testing is a special pair of glasses with flashing lenses that switch between clear and blacked out. The device provides distraction for the brain’s visual cortex while still allowing a patient to easily move around to complete balance exercises, treadmill running, and strength training. The glasses preoccupy a patient’s eyes, knocking down visual processing just enough to force the brain to react instinctively again—the sensory system the brain was meant to use.

We’re finding that another powerful tool is Google Cardboard. We take a panoramic picture of a soccer field and load it to a phone that we place in a Google Cardboard virtual reality headset. The system can be purchased for $15, but it’s incredible—the patients can look around as if they’re on the field, but they’ve never left the clinic. So the cue of seeing the legs disappears, but the mind still gets a realistic sense of context and a more natural and helpful visual environment.

Such distractions allow the brain to rewire back to its normal state—we don’t allow the eyes as a cheat and instead teach the brain to move the knee instinctively, again.

To date, clinicians, physical therapists, athletic trainers, and physicians have not necessarily been aware of the mental component of ACL rehab. We’ve tended to focus on joint strength or stability. Now we’re starting to realize that we must also consider the brain when we address musculoskeletal, orthopaedic-type injuries.

If you’ve had an ACL injury, recognize that during recovery, your brain may have taken the easy way out. Consider finding a rehabilitation specialist who can help address both the physical and mental challenges you may face and retrain your mind to just let your knee do its job.